21st July 2025

Some observations on the allure of the Sea, this quality being found in its expanse and unknowability, together with an episode of 16th century Piracy

Lately, I shared a reading of a chapter from Moby Dick about the cultural significance and horror of whiteness. While the novel is captivating in part because of the unrelenting intensity of Melville’s style, I think its effect also owes much to its nautical setting. In the same way that Melville describes whiteness as awful (read: awe-full) because of its void-like emptiness, so the sea — vast, amorphous, uninhabitable — is as terrifying as it is mesmerising. Thus, Melville also writes:

We know the sea to be an everlasting terra incognita, so that Columbus sailed over numberless unknown worlds to discover his one superficial western one … forever and forever, to the crack of doom, the sea will insult and murder [man], and pulverize the stateliest, stiffest frigate he can make … Yea, foolish mortals, Noah’s flood is not yet subsided; two thirds of the fair world it yet covers.

Melodramatic, perhaps, but essentially the same sentiment has been expressed by countless others, such as Rachel Carson in her landmark cultural study, The Sea Around Us (1951):

The sea has always challenged the minds and imagination of men and even today it remains the last great frontier of Earth. It is a realm so vast and so difficult of access that with all our efforts we have explored only a small fraction of its area. Not even the mighty technological developments of this, the Atomic Age, have greatly changed this situation.

What is the fraction we have explored, exactly? Although we have low resolution maps of the complete seafloor thanks to satellite imagery, only 26% of it has been mapped to the extent that we can talk about its geography and locate objects like shipwrecks, while as little as 0.001% of it has actually been seen by human eyes (and this is just the floor, to say nothing of the whole volume). Hence research vessels are still stumbling upon new mountains as large as the Alpine one shown below, and 2,000 new marine species are documented every year.

It’s tempting to think of the sea as being to Melville what outer space is to us: the furthest place we can reach with our technology, intimidating and impractical to explore, far too large to understand, and yet full of the vague promises of colonisation. But space hasn’t given us a new frontier so much as it has merely stretched the one we still have — building cities on the open ocean is no less difficult than building them on the moon, and space does not threaten to encroach upon human settlements, while many are likely to be claimed by rising seas this century.

Nonetheless, as primal as this feeling is, when we imagine early humans standing on the edge of Africa, looking out onto the forbidding waves, we will suppose them to have been moved in a totally different way than we are today, thanks to our efforts to conquer the unconquerable through industry and invention. This is why I particularly enjoy the paintings of John Atkinson Grimshaw as compared to ordinary seascapes, as he depicts ships at the docks, looming on the margins of civilization — they are at once the emblem of empires asserting themselves abroad and a reminder of the squalor of life away from land.

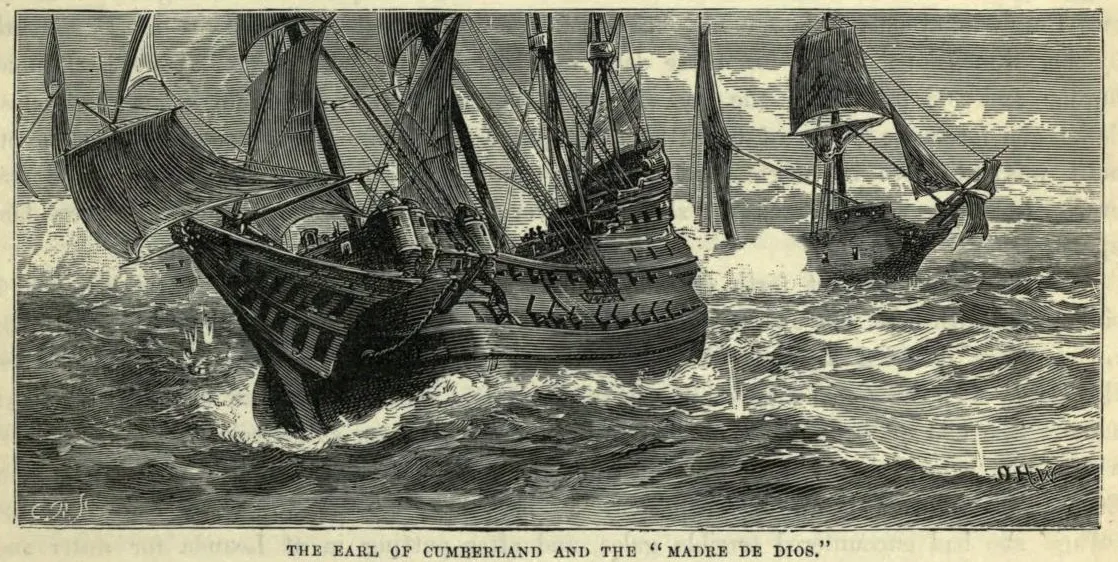

By coincidence, I recently read of the naval Battle of Flores in 1592, which taught me some of the strategy and precariousness of seafaring. In May of that year, the English put together a private expedition of ships, probably secretly funded in part by Queen Elizabeth I, with the intention of pillaging Spanish and Portuguese fleets in the Atlantic. By June, the English had already succeeded in capturing some Spanish vessels and they had tortured prisoners for information about what would become their greatest prize: the Madre de Deus, one of the largest sailing ships ever built, a 1,600-ton Portuguese carrack with 32 guns.

With knowledge of its route and plenty of time, the English raided nearby villages in the Azores archipelago for supplies and then patrolled a corridor between the islands for a month. Eventually, the Madre de Deus was spotted sailing into their trap and the sailors realised its massive size — at least three times larger than their own largest ship. The Madre de Deus came under fire from five English vessels in sequence, each one dwarfed by their rival. But unlike with Ahab’s whale, the attackers didn’t want to harm their prey too severely or they wouldn’t be able to return its bounty to England.

After many hours of fighting, one of the English ships crashed into its target and the sailors boarded it in the dark of night, prevailing over the Portuguese in bloody hand-to-hand combat. The bested survivors were sent ashore, while the English made repairs and began their journey home. Estimated to be the second largest captured treasure after the deceit and ransom of Atahualpa, an inventory of the cargo listed:

pepper, cloves, maces, nutmegs, cinnamon and greene ginger … benjamin, frankincense, Galangal, mirabilis, aloes zocotrina, camphire … silks, damasks, taffatas, alto bassos, that is, counterfeit, cloth of gold, unwrought China silk, sleeved silk, white twisted silk, curled cypresse … book-calicos, calico-launes, broad white calicos, fine starched calicoes, course white calicos, brown broad calicos, brown course calicos … canopies, and course diapertowels, quilts of course sarcenet and of calico, carpets like those of Turky; whereunto are to be added the pearl, muske, civet, and amber-griece. The rest of the wares were many in number, but less in value; as elephants teeth, porcelain vessels of China, coco-nuts, hides, ebenwood as black as jet, bested of the same, cloth of the rind’s of trees very strange for the matter, and artificial in workmanship.

To give some sense of the scale, the pepper alone amounted to 425 tons and the value of the whole lot was equal to half of the English treasury at the time. The Madre de Deus reached south west England a month after its capture and was swarmed by people from as far away as London (more than 200 miles), who seized, stole, bought and sold goods that were by law owed to the Queen. Sir Walter Raleigh was sent to bring order to the chaos and, though much of the treasure was unrecoverable, the Queen made something like a 20 times return on her investment. Soon afterwards, the influx of these luxuries caused a crash in the London spice market.

There are secondary sources for the event which contain all sorts of wonderful detail. Thus, in The Sea: Its Stirring Story of Adventure, Peril and Heroism (1877) by Frederick Whymper:

For the times, the prisoners were treated with great humanity, and surgeons were sent on board to dress their wounds. The captain [of the Madre de Deus], Don Fernando de Mendoza, was “a gentleman of noble birth, well stricken in years, well spoken, of comely personage, of good stature, but of hard fortune. Twice he had been taken prisoner by the Moors and ransomed by the king; and he had been wrecked on the coast of Sofala, in a carrack which he commanded, and having escaped the sea danger, fell into the hands of infidels ashore, who kept him under long and grievous servitude.”

And the 19th century Dictionary of National Biography says of Sir John Burgh, one of the most important combatants in the battle:

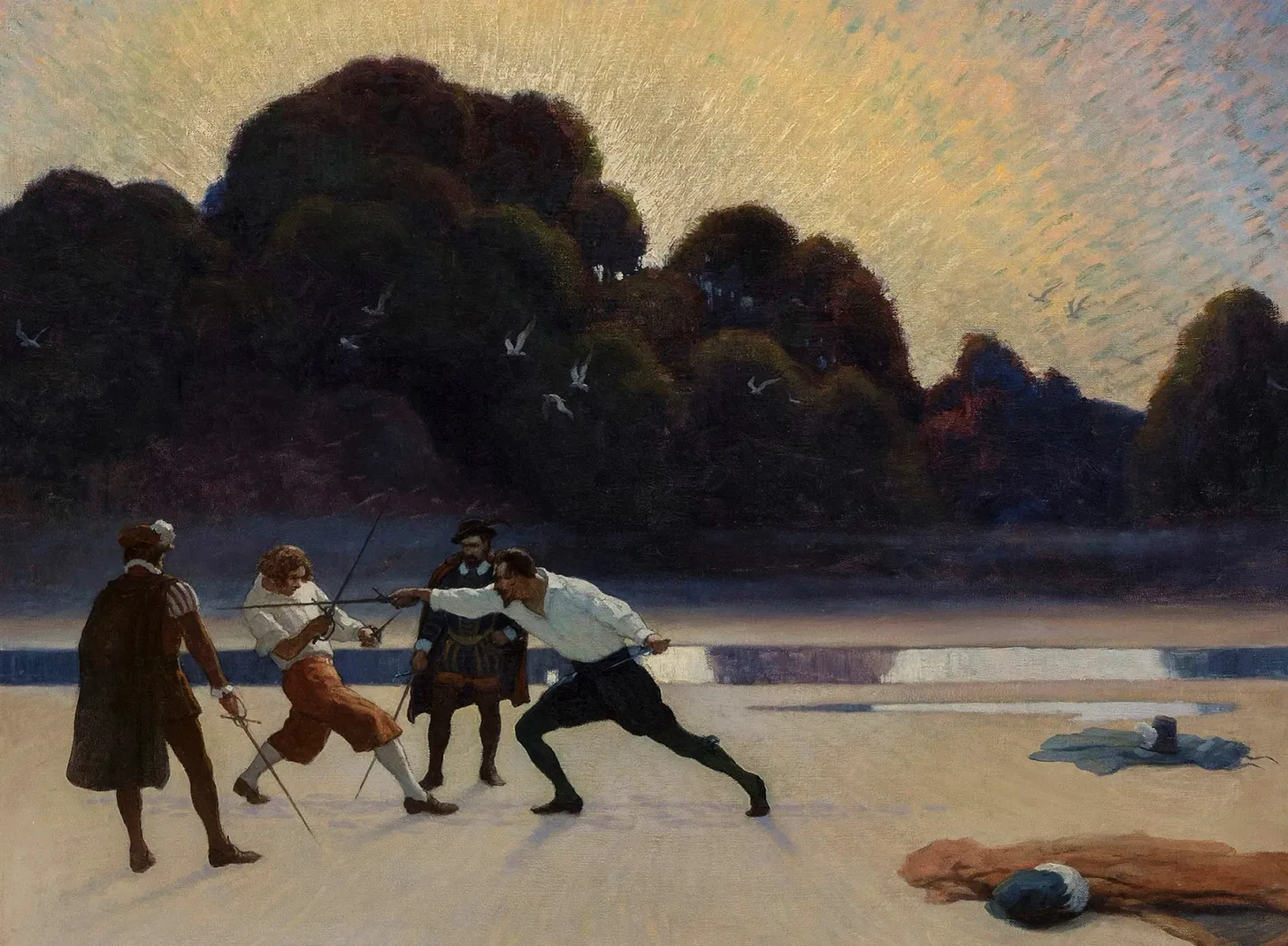

The disputes as to the shares of what remained [of the Madre de Deus plunder] ran exceedingly high … Sir John’s share was but small, and was declared by the commissioners to be within reason; but the disappointed men refused to accept this decision, and much recrimination followed. Out of this probably arose a quarrel with Mr. John Gilbert [which] resulted in a challenge sent by Burgh, in which he desired his antagonist “not to use boyish excuses, or he would beat him like a boy”. Gilbert accepted the challenge, claiming the choice of weapons and choosing single rapiers. In default of exact evidence the agreement of dates leads to the conclusion that the duel took place, and that Burgh was killed.

An inventory of early modern ships

barque: an etymological intrigue, since barque came to English from French via Latin via the Celts (a rather long journey)

brigantine: named after the Italian word for robbery and plunder, it was a favourite of pirates for its speed and ease of handling

caravel: used by the Portuguese and Spanish for voyages of exploration, we remarkably know less about their construction than that of ancient Greek and Roman ships

carrack: a precursor to the galleon and an important trading ship for Spain and Portugal, the first ship to circumnavigate the globe was a carrack (the Victoria)

clipper: a mid-19th century ship designed to be fast for a better tea trade with China and quicker travel to America and Australia

corvette: a small warship in a supporting role, the word still applies to modern ships with the same function and it’s where the sports car gets its name from

frigate: a bigger brother to the corvette, the meaning of the word is very loose but it’s generally a powerful but manoeuvrable warship

galleon: a technological advance on the carrack, galleons were armed cargo vessels often used as auxiliary warships

patache: vessels mainly used by the Spanish in the 15th-18th centuries for efficient surveillance of their colonial territories

ship of the line: a warship designed specifically to engage in ‘line of battle’ tactics, where columns of opposing ships fire cannons along their broadsides